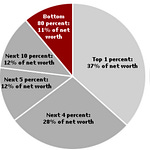

As a life-long anti-capitalist with a background in the global justice movement, I don't know how it took me so long to notice this, but the modus operandi that gigantic corporations like Spotify and Facebook employ in their efforts to monopolize eyes, ears, and industries is essentially the same as that of the IMF, with its history of keeping poor countries in a perpetual state of "development" through debt peonage.

I hope most of you are wondering what the hell I'm talking about here, because I'm going to explain. I also hope some of you are having a light bulb moment like I just did, because the comparisons between the IMF and these corporations is obvious as soon as you engage in the intellectual exercise of making them, if you know enough about the operations of all of these predatory entities.

I'm a professional musician, and I spend a lot of time thinking about Spotify, engaging with the platform in various ways, and being impacted by it tremendously.

It's far from a straightforward relationship between me and Spotify. As with, say, borrowing a billion dollars, it's not just an exploitative relationship between lender and borrower, it's a two-way street. There are great potential benefits to being able to borrow a billion dollars, depending on the terms of the loan and what you might be planning on doing with the money.

If you're a poor country in need of a billion-dollar loan, for a lot of countries there has historically been just one option to borrow from. The IMF's loans came with lots of strings attached, that would mean the borrower country risked becoming dependent on more loans, and would be structurally unable to repay them, because of the strings that were attached to the loans in the first place, such as the requirement that the country privatized ownership of industries or natural resources that could have made the country rich, if they had not been sold at pennies on the dollar, under duress.

But even if you weren't a corrupt dictator looking to increase the size of your Swiss bank account, if you were running a poor country, you might also take the loan, after the economists explain to you how much better your country will be doing once it has a nice new highway or a new hydroelectric dam. The loans and what you can do with the money can look really good. And if the money is coming from the only game in town, you tend to play by their rules.

With giant, global corporations like Facebook and Spotify, they're not aiming to get national governments hooked in to their services, so much as the ears and eyes of everybody living on the planet. The strategies are aimed at individuals, our desires and our needs, and getting us sufficiently hooked into their matrix that they essentially become monopolies that we can't afford to live without relating to on their terms. Especially, in the case of Spotify, if you're a professional musician -- or perhaps someone who used to dream of being one.

Everyone who is old enough probably remembers when Facebook first hit the scene, and when they started using it. If you're someone involved with promoting your music or trying to spread the word about anything, you probably remember how useful the platform was in the earlier years of its existence. You'd post something, and if you had a lot of followers, a lot of people would see your post, and do things like buy the album you were posting about, or come to the show you were promoting.

It was so good, so useful, so rewarding that you may have stopped maintaining an email list, just as you stopped maintaining a mailing address list long before. You may have stopped communicating with anyone by email altogether, and stopped going to websites that weren't Facebook pages. You may have maintained accounts with other platforms that started out as similar ones, like Friendster or MySpace, but when everyone migrated to Facebook, you did, too. And then they became the monopoly that they are today.

At which point, the rug was yanked from under our collective feet, but it was too late to do anything about it. The trick is, most people didn't necessarily notice. Most people use Facebook to keep tabs on what their friends are posting about, and share posts themselves. They may notice that some posts get more engagement than others, but their livelihood isn't dependent on it.

For the minority of us for whom this is life or death stuff, we noticed when Facebook pulled the rug out, right away. Suddenly it didn't matter whether you had a big following, no one was going to see your posts unless they had nothing to do with promoting a gig or an album, but were about a vacation or a wedding or a baby. If you wanted people to see your posts about the tours or albums, you now would have to pay -- "boost," they call it. They started that as soon as they became a monopoly, and it's been their MO ever since.

Spotify has had its own trajectory, but the end goal of becoming a monopoly that makes and changes the rules as they see fit is the same.

At the beginning their pitch to musicians was hey, people are pirating all of your music anyway, but with legal streaming platforms like ours, you'll at least get paid something for it, even if it's not much.

This pitch was problematic to begin with, because it operated on the assumption that all recording artists, from the pop star to the shoe-string garage band, were having the same experience with music piracy, which was most definitely not the case. From my personal experience, and I think it stands true for many others, I was still selling plenty of CDs right up until 2013, when Spotify started their Free Tier.

Once Spotify became the dominant player in the music streaming business, they had enough clout to make a deal with the Big Three record labels, to sign them and their artists up for the Free Tier, by giving plays of Big Three artists a bigger percentage of the streaming revenue.

By the time Spotify started their Free Tier and devastated the independent music industry globally overnight, it was already too late to fight back by encouraging people to use different platforms or whatever. Spotify set the standard, and soon everyone else was forced to follow suit, to one degree or another.

Now, today, living in this world so dominated by one Stockholm-based music streaming platform for the past eleven years or so, even here in the ruins of the indy music biz, the influence of Spotify continues to be all-encompassing.

It may be that there is very little money to be made from recording albums and putting them out into the world under the supremely unequal arrangements Spotify has pioneered, as far as selling music goes -- but what about having listeners at all?

Everywhere I go on tour these days, when I ask young people how it was that they first heard my music, if they can pin it down, the most common answer is "Spotify." When I drill deeper I usually learn that what this means is actually it was Spotify's song recommendation algorithm that directly led them to me. They may have been listening to Phil Ochs, Billy Bragg, or the Mountain Goats, but whoever it was, Spotify saw fit to stick one of my songs in next, they liked it, and soon became more intentional listeners of my music.

Spotify tells me that my new album, just out on streaming today, has been listened to over 1,500 times in the first 24 hours. Spotify tells me that of my 17,000 listeners on the platform last month, 5,000 of them were first-time listeners.

That's very significant. Now what if they were to take all of that away? Maybe next month I'll have 12,000 listeners, and those 5,000 new listeners Spotify sent my way will be sent elsewhere.

In fact, my fellow musicians especially, if there are any left alive reading this, that seems to be exactly the sort of thing Spotify has in store for us.

Now that their venture capital, monopolistic practices, and absolutely brilliant music recommendation algorithms have put them into the position of being by far the most dominant music streaming platform in the world, they've introduced their Campaign Kit. And all of the campaigns in Spotify's new Campaign Kit are designed for artists or corporations who want to forego earnings, or pay money, in order to have their music get more attention on the platform.

Now that Spotify is in control, they can afford to allow their algorithm to start sucking a little, in order to make more money from those willing or able to pay more to get played more, in order to develop their audience that way.

If Spotify's new Campaign Kit or things like it becomes widely adopted, and there are enough artists or corporate representatives thereof who are willing to forego streaming revenues or pay to get played on the platform like these promotional tools are designed to facilitate, the great recommendation algorithm will inevitably get worse and worse. But as long as Spotify can keep their platform popular enough to maintain their monopoly while squeezing as much money as possible from the artists that are the basis for the platform's existence, then they'll make their investors happy -- at the expense of the rest of humanity, recording artists in particular.

If you're looking for hope at the end of this transnational corporate monopoly tunnel, you might want to join United Musicians and Allied Workers like I recently did. The hope that does exist all lies within the realm of solidarity, organizing, and collective action.

Share this post